Listening to that album for the first time on an old record player which I shared with thirty other members of the Junior Common Room in my house at school, I was overwhelmed. Brought up on classical music and musicals, listening to pop on Radio Luxembourg (yep, I can spell

K-e-y-n-s-h-a-m), this was revelatory.

Only two of those songs were original in the sense that they were written by Bob, Song to Woody and Talkin’ New York . The rest were what we we came to know as covers, but we didn’t use that term in those days. This was still a time when lyricists and composers sat in garrets somewhere collectively known as Tin Pan Alley and wrote songs which were subsequently recorded by performers, the ‘talent’. And folkies always stole from each other and from the tradition. Talent borrows, genius steals.

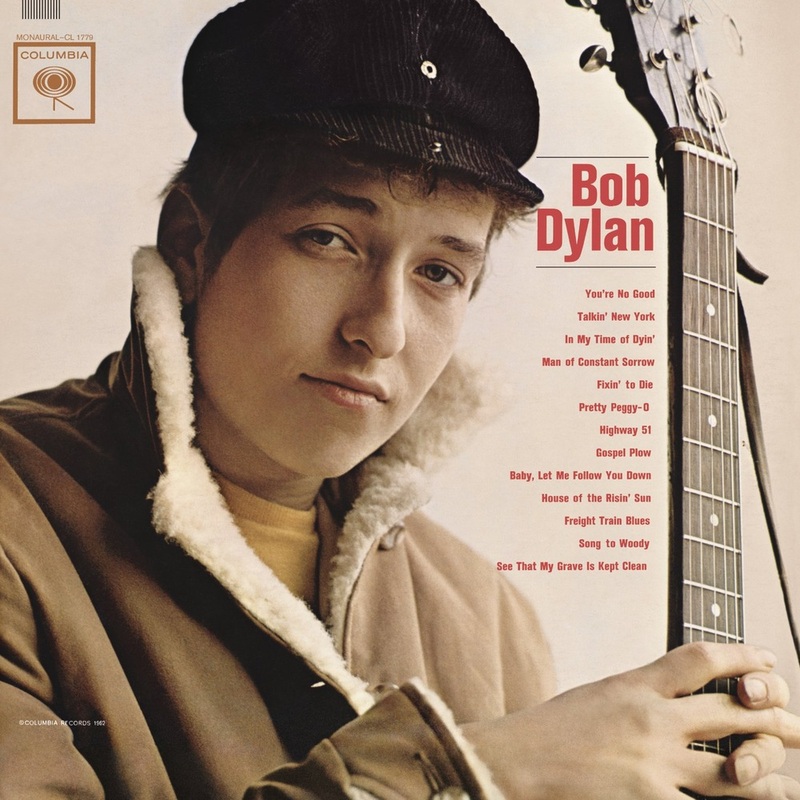

The extraordinary thing about this album was that the voice and the style bore no relationship to the (famously reversed) portrait on the album cover.

The portrait showed a young cherub. The voice was old. Old even by the standards of the folkies that we had heard in other contexts. Old by the standards of the singers we heard on the radio. There was an authenticity, a sense of tradition, an originality, which impressed us young 13 year olds in a way which few albums have since.

Bob Dylan was, in the mythology of Bob, recorded in a couple of short sessions and cost “around $402”. Yet it is, in the words of Michael Gray, “a brilliant debut, a performer’s tour de force”.

Bob has said that he was hesitant to record any more of his own songs because he didn’t want to give too much of himself away. But, whether he wished to or not, he gave a great deal away.

He showed himself to be a man with a sense of purpose, an instinctive understanding of “the poetry of the blues”and its place in the musical and American traditions. His producer, John H Hammond, quotes him as refusing to re-record, that he would never do the same song twice – a philosophy which irritated Daniel Lanois 37 years later during the recordings of Oh Mercy.

He wouldn’t learn from his mistakes because, in his view, they were not mistakes. They were authentic performances, each as valid as the other.

Which is pretty much how he has continued to work. Why each album is a new road. Why each gig reveals or hides another element of his music and himself.

Twenty years old, yes. But even then, he knew he was “just headin’ for another joint”.

We may be ecstatic or disappointed, and I have been both too many times to count.

Over the last 52 years, I have measured out of my life, not in coffee spoons, but in Dylan albums and Dylan shows. The last time was a disappointment (my problem in retrospect) but I too am with him on the road, just headin’ for another joint, a new song or a new interpretation of an older one.

On the 19th of March 1962, I would have settled for a hell of a lot less. And could never have imagined that I would be listening with pleasure and delight to that album in my 65th year.

But I am.

Nevertheless, by the time the album was released, Bob was already headin' for another joint. As you can hear here - also from 1962.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed