The story goes that a High Court judge, exasperated by a line of questioning from FE Smith, told the barrister that having heard the evidence, he was “none the wiser”.

“No, my lord” replied Smith, “but far better informed”.

I was reminded of this watching our friend Anthea Callen on Fake or Fortune?, a BBC TV programme which follows the progress of authenticating works of art. This week featured Degas, one of Anthea’s specialist subjects.

Of course, the point of the programme is to pronounce the picture genuine and thus turn a painting worth a few hundred into something which the owner can sell for hundreds of thousands, so any perceived reluctance is a potential issue for Fiona Bruce, the ubiquitous presenter. So when Anthea refused to give an unconditional guarantee, Bruce told her that “connoisseurship is an opinion, and there will be several opinions.”

I will treasure Anthea’s response for some time. “Of course” she said. “But some people are more informed than others.”

For my part, I didn’t think it was a particularly good painting, certainly not as good as that of which it was possibly a copy or a precursor. But one of the issues I have with the art market is that a painting is good or bad, worthless or priceless, according to its maker.

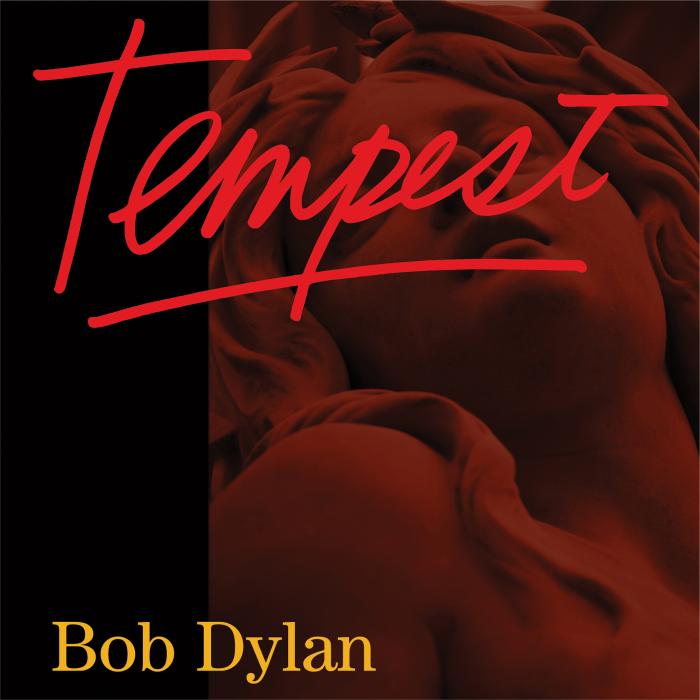

It doesn’t work in other fields. As I listen once again to Tempest, I reflect that Bob’s authorship does not bestow greatness per se. He has written some spectacularly bad songs in his time, and they are no better because he wrote them. Tempest received pretty much unanimous praise from the reviewers, much of it based on a single sneak preview, and much of it influenced by one of the most intensive marketing campaigns for any Dylan release.

There has been no shortage of phrases to sing his praises.

But like Anthea and her Degas, I have not rushed to judgement. I have now spent two weeks with Tempest. And I am finally ready to confirm that this is an extraordinary album. But not without flaw.

I am, for example, skipping the first and final tracks on most plays. The first is a good song, but is out of kilter with the rest of the album. The lyrics are by Robert Hunter, and would be more appropriate for the other Bob, Weir, in his cowboy mode. The final song is certainly a “heartfelt tribute”, but so was my bursting into tears when I heard of John’s death: heartfelt but not art.

The core of the album, however, from Soon After Midnight through to the title track, is uniformly magnificent and uniformly dark. If it was once “not dark yet”, it certainly is now. His epic narratives are now populated with “flat-chested junkie whores”, corrupt financiers and politicians. They are punctuated with lines of Brechtian viciousness. In no song is there any sense of redemption. It is remorselessly bleak. Everything is broken.

As he sings in Early Roman Kings: “I can strip you of life/strip you of breath/ship you down/to the house of death.”

In the “dark illumination” of this album, Bob has shipped us down to a Desolation Row for our times, and it is a morbid and frightening experience to which we will return again and again.

Today’s listening: Still Tempest, but this morning paying particular attention to the excellence of Tony Garnier, whose upright bass is masterly and (rightfully) prominent throughout.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed