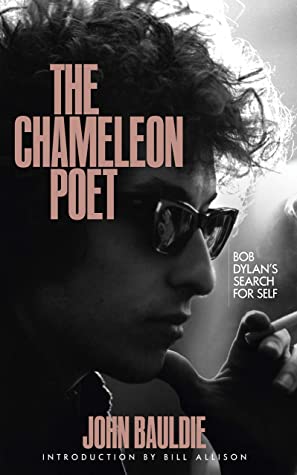

The parallel is clear. John Bauldie’s posthumously published book, titled The Chameleon Poet and sub-titled Bob Dylan’s Search for Self is a tardy but nonetheless interesting contribution to the faux Dylan-Keats debate of decades ago, a debate in which I engaged at the time but always with an understanding that, although I was a lover of Keats and remain so to this day, the quarrel was of no relevance to an appreciation of either. Then, it was about defending the genius of Dylan against the snobbery of people like AS Byatt and, crucially, defending the song against the poem. It was about defining poetry.

Bob of course, Bob being Bob, he was ambivalent. “Yippee, I’m a poet and I know it” he sang, before adding (just in case he was being taken seriously) “Hope I don’t blow it!” And when asked directly if he regarded himself as a poet, he replied “I think of myself as just a song & dance man”. Michael Gray, the pioneer of Dylan studies, seized on this conceit in his seminal triptych, Song & Dance Man, the first volume of which was published as far back as 1972 and in which I am not aware of any mention of John Keats.

According to Bill Allison’s excellent (and for me, informative) introduction to The Chameleon Poet, Michael’s first volume inspired Bauldie. Reading it, he realised he wanted to be more of a Dylanologist than a Bobcat (although he is credited with the coinage of the latter term, which refers to those who follow the shows as compared with the desk-bound scholars). Certainly, Bauldie makes no reference to shows, to music, to performances. His emphasis is almost exclusively on textual analysis, including the movies and - importantly - Bob’s writings on the back cover of the sleeves. It's practical criticism. Throw in his degree in English and his experience as a teacher of English, and you have the nub of Bauldie’s approach.

It is, in many ways, a schoolmasterly book. You see how I started this piece talking about Keats and only by association moved onto Bob himself? That’s a trick Bauldie uses in this book as he must have done many times in classrooms as both student and teacher. One chapter, ostensibly concerned with Bob’s early work, begins with a lengthy exegesis of King Lear. Others reference Hesse, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Jung. Even if one didn’t know about Bauldie’s untimely death, one could make an informed guess at the date of the manuscript of this book.

Bauldie was older than me. By five days. We were both born in the last days of the summer holidays in 1949. We both combined our love of Bob with support for under-performing football teams. His interests were my interests at that time and the compare-and-contrast methodology with which we had been imbued is a way of thinking and explaining adopted by all of us in and out of the classroom.

He is not as meticulous in his readings as Michael Gray, who, in turn, is not as meticulous as Christopher Ricks. But who is? Nevertheless, there are some keen insights here. He is particularly good on Planet Waves and John Wesley Harding. And, passim, he is excellent in his distinguishing of the noumenal Bob from the phenomenal, the inner from the outer, the masked and anonymous from the simple and direct.

I wish I had known John Bauldie. But I know him well enough now through this book. And I am reminded of one of my favourite Bob stories.

“You don’t know me, but I know you” said a fan, outside a show.

“Let’s keep it that way” said Bob.

Today from the everysmith vaults: Bob’s first show back on the road, in Milwaukee, on Tuesday night. A wonderful show, with eight songs from Rough & Rowdy Ways and the sound of Shadow Kingdom. It’s only been in the vault for 48 hours but it is currently playing for the fourth time around.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed