I have the complete set in the blue Wanted Man binders at eye level on the shelves behind me as I type, next to Christopher Ricks and Paul Williams and Michael Gray and Clinton Heylin and Andrew Muir and Anthony Scaduto and Howard Sounes and Robert Shelton and Greil Marcus and, of course, Bob himself. They deserve their pride of place.

It was in the pages of The Telegraph that I first encountered the writing of Roy Kelly. And I didn’t like it. I didn’t want to read about this guy’s relationship to Bob – I could get that kind of thing at home. I wanted the scholarship, the academic paraphernalia, of serious Bob studies.

Things came to a head with the publication of a long piece entitled Now and Again: The Ballad of a Then Man. I hated the title. I hated the fact that, although it was written in the third person, it was all about him. I hated his atavar, Ron Bobfan. I ranted for days about it. It was self-centred, self-absorbed and self-indulgent.

And then, someone pointed out that it could be me.

To this day, I do not think that The Telegraph was the appropriate vehicle for autobiography. (But Roy did. And more importantly, John Bauldie did.) I am, however, more than happy to accept that there is a place for this form of Dylan-related memoir. Which is why I welcome Roy’s more honest, first person autobiography, published shortly before Christmas in time to give me the time to read it.

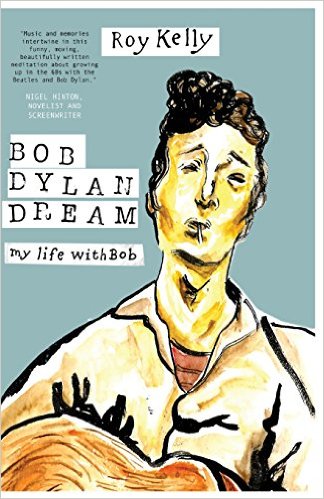

Bob Dylan Dream: My Life with Bob is fascinating. It appears that we were of the same age (born in 1949) but our upbringings could not be more different: he a son of Walsall, I the eldest child of a service family and sentenced from an early age to a boarding school life.

I would swap my first eighteen years for his in an instant.

But what we did have in common was music and literature (though in his case not sport, a bizarre omission for the age and the time). I, bumming around London in school holidays, found the folk club Les Cousins and heard the likes of Davy Graham and heard of this American guy Bob Dylan. I bought that first album and, back at school, fought for time on the Junior Common Room record player to play it. From that moment, my friends were those schoolmates who ‘got it’. About half a dozen of us. And, later at university, all my friends related in one way or another to Bob. Some were old Stalinists, who loathed the new electric Bob; others were those who not only loved the post-1965 Bob but also embraced the Dead and the Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Velvets and the Soft Machine.

As he relates (confesses?), Roy didn’t get the Dead, even though he had a friend and mentor who did. This is, for a man who subsequently earned much of his living as a music journalist, a grave omission; which is only redeemed by his admiration for A Dance to the Music of Time, Anthony Powell’s never ending tour through five decades of the last century.

Powell deals with a generation before and a class or two above both of us. But in the sequence we saw lives with which we wished to identify and perhaps even emulate. Roy has gone further in the latter respect, writing poetry which never excites me but always leaves me nodding in agreement and approval, a latter-day X Trapnel. But he has also lived, by his account, a happy and rewarding life and pursued a career which has made him a living from his passion.

His book is a record of this life and this career. But his title is misleading. For vast tranches of the book, Bob does not appear and nor does Ron Bobfan, a conceit with which I still do not empathize and which – stubbornly – I do not recognize and shall not acknowledge. For me, these Bob-less chapters are the most interesting because they relate to a life which is wider, broader, more diverse; a life which is not mine. They relate to an open society.

The Bob world is a closed world. I was merely a reader of The Telegraph, but I was occasionally present in a hotel bar close to the Hammersmith Odeon in the ‘90s where and when The Telegraph gang met before gigs. Before or after the Birmingham and Manchester shows, my gang and I would drive down the M40 for the Hammersmith gig and take a glass before the show. We knew by sight many of The Telegraph lot. We would eavesdrop on their conversation and envy them their front row tickets, their access to Bob and his world. We wanted to be part of it too.

That’s the thing with the Dance and with The Telegraph. Both describe a closed world, an almost suffocating world. Roy was right at the centre of this, but in this book he eschews all that stuff and opens our eyes to a different world in which Bob is a vehicle and a means for advancement; indeed, almost a metaphor for such. I enjoyed it for its parallels with my own journey, especially the moment when the children (and in my case, the grandchildren also) suddenly get Bob, when we know that as parents, we have handed on something important.

But principally I love its small details, its honesty and straightforwardness. Unlike most autobiographies, I believe it.

It’s not the virtual truth of Ron Bobfan. It is true. And it is beautifully written.

I commend it to you.

Today from the everysmith vaults: Taking a brief break from Chris Forsyth in favour of Bob. Not the Christmas album (about which Roy is wrong) but World Gone Wrong (about which he is 100% right).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed